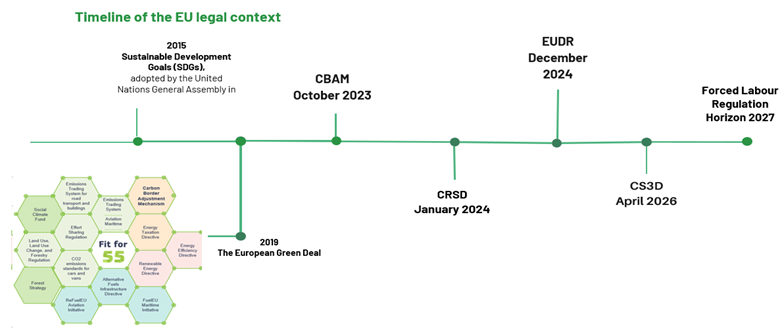

The European Union (“EU”) has been a driving force in environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) regulations. The EU’s environmental policies are part of a broader commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals (“SDGs”), adopted by the United Nations General Assembly[1] in 2015. These goals address critical global challenges such as climate change, environmental degradation, and social inequality.

In 2019, the EU announced the European Green Deal, setting an ambitious target of achieving zero net greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions by 2050. This initiative underscores the EU’s dedication to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent.

To support this goal, the EU has implemented a series of regulatory measures designed to promote sustainability and mitigate the impacts of climate change, including:

- the Directive 2022/2464 on corporate sustainability reporting (“CRSD”),

- the Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 on the making available on the Union market and the export from the Union of certain commodities and products associated with deforestation and forest degradation (“EUDR”),

- the Regulation (EU) 2023/956 establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism (“CBAM”),

- the proposed Regulation (EU) on prohibiting products made with forced labour on the Union market (“Forced Labor Regulation”).

Together, these initiatives seek to drive a more sustainable economy by ensuring that companies adhere to stringent environmental standards and provide clear, reliable information to investors and consumers.

While these regulations are EU-driven, their impact extends globally. Companies worldwide that wish to do business in the EU or with EU-based companies must adapt to these standards. This requirement to adopt the EU standards has a cascading effect, pushing global supply chains towards greater sustainability and ethical practices.

The ASEAN Taxonomy Board (“ATB”), set up under the auspices of the ASEAN Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meeting also participates to the creation of ESG guidelines by developing, maintaining and promoting a multi-tiered guide on ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance (“ASEAN Taxonomy”) which identifies economic activities that are sustainable and help direct investment and funding towards a sustainable ASEAN.

The ASEAN Taxonomy (Version 3 published on 27 March 2024) is an overarching guide for all ASEAN Member States (“AMS”), complementing their respective national sustainability initiatives and serving as ASEAN’s common language for sustainable finance. It is designed to ensure that AMS have a framework that suits their economic and social structures that other frameworks may not be able to address.

In this newsletter, we aim to provide:

- a better understanding of the EU’s sustainability reporting landscape;

- how it compares to five key Asian jurisdictions: China, Indonesia, India, Vietnam and Singapore; and

- steps to take to comply with the new EU regulations.

Below is a snapshot of China, India, Indonesia, Singapore and Vietnam national approaches by our Asia based team:

I. Understanding the EU’s sustainability reporting landscape

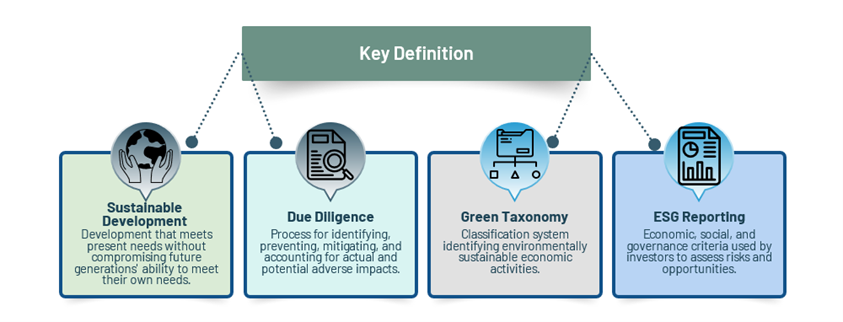

1. Key definitions and timeline

A. Key Definitions

2. Timeline of the EU legal context

3. CSRD

The CSRD is a critical part of the EU’s environmental strategy. It replaces Directive 2014/95 on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups (“NFRD”) and aims to enhance the reliability and accessibility of sustainability information through standardized and comprehensive reporting. Since 1st January 2024, the CSRD mandates companies that meet certain thresholds to report on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, integrating sustainable finance and green taxonomy principles. It introduces the concept of “dual materiality,” ensuring that companies report on how sustainability issues affect them and their impact on society and the environment. This standardized reporting aims to improve the reliability and transparency of sustainability data, guiding investors, and stakeholders towards more informed decisions.

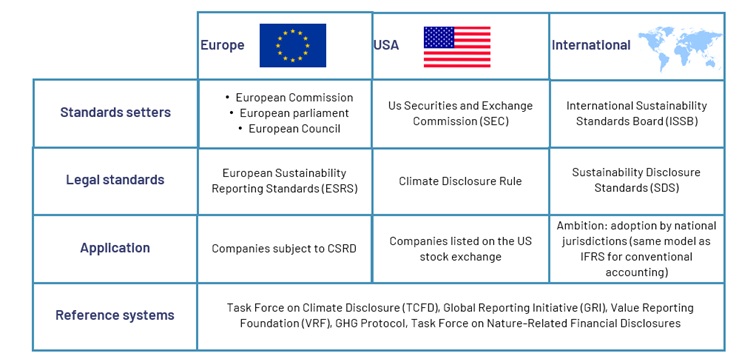

A. Comparison with other international initiatives

In comparison with the other international regulations, the CSRD can be considered as the most ambitious of the ESG information standardisation initiatives.

B. Scope of application and road map

CSRD will be implemented in phases as illustrated below:

| Large Public Interest Entities (PIEs) with >500 Employees (Already Subject to NFRD): | Large Companies Newly Subject to CSRD (Including Large Listed Companies with < 500 Employees): | Listed Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): | Non-European Companies Meeting CSRD Conditions: |

| 2024 – Immediate Action: Begin preparing for CSRD compliance based on cross-sector standards. | 2024/2025 – Preparation Phase: Prepare for CSRD compliance based on cross-sector standards. | 2026/2028 – Preparation and Transition Phase : Prepare for CSRD compliance based on specific ESRS standards. | 2028-Preparation Phase : Prepare for CSRD compliance based on specific ESRS standards. |

| Key Steps: Assess current sustainability reporting and identify gaps.Update internal processes for data collection and reporting.Allocate resources and designate teams for CSRD compliance.Engage with stakeholders to understand their expectations.Conduct a materiality analysis to identify key sustainability issues. Outcomes: Establish a CSRD compliance framework.Initiate data gathering and reporting activities. | Key Steps: Familiarize with CSRD requirements and guidelines.Conduct a gap analysis comparing current practices with CSRD requirements.Develop a roadmap and timeline for CSRD implementation.Enhance internal capacity for sustainability reporting.Consider engaging external experts for support. Outcomes: Gain a clear understanding of CSRD obligations.Begin internal preparations for compliance. | Key Steps: Monitor developments in ESRS standards and guidelines.Evaluate readiness for sustainability reporting.Implement changes to internal processes and systems.Train and support relevant staff members.Develop a communication strategy for stakeholder engagement. Outcomes: Align internal systems with CSRD requirements.Begin sustainability reporting activities | Key Steps: Understand CSRD requirements and implications for non-European companies.Assess operations and supply chains comprehensively.Collaborate with European subsidiaries or partners for data gathering.Develop strategies to address compliance challenges.Establish communication channels with regulatory authorities for guidance. Outcomes: Develop a CSRD compliance plan.Initiate necessary actions to meet requirements. |

C. Controls and penalties:

Statutory auditor or audit form must carry out the assurance of sustainability reporting. As most of the European regulations, each member state must ensure that the provisions of the directive are implemented by providing an effective, proportionate, and dissuasive sanction to auditors and audit firms.

3. CBAM

The CBAM aims to prevent carbon leakage by ensuring equivalent carbon pricing for imports and EU products. It gradually phases out free allowances under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) and introduces a carbon pricing mechanism for imports, ensuring that non-EU products are not favored over EU products. This mechanism supports the goal of climate neutrality and aligns with international climate commitments, such as the Glasgow Climate Pact and the Paris Agreement. These regulations aim to reduce the EU’s carbon footprint and promote sustainable economic activities that do not exacerbate climate change.

A. Scope of application:

The CBAM creates new regulatory obligations for importers and will initially apply only to the following sectors: cement, aluminum, nitrogen fertilizers, electricity and hydrogen.

The CBAM places the main liability on the EU importer, however the regulatory obligations will require concerns all economic operators and strong cooperation between producers or suppliers and buyers involved in the supply chain concerned in international trade from or to of products imported in the EU. The CBAM provides a transition phase and an effective operating period:

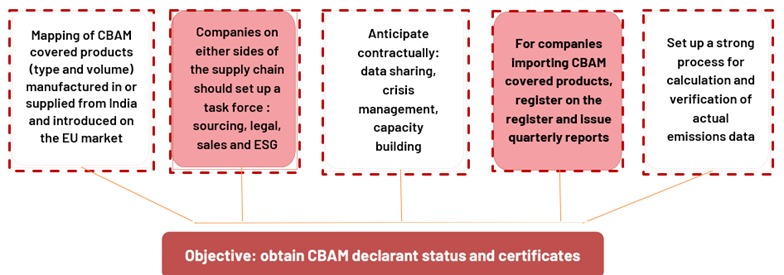

B. Obligations under CBAM

First, every importer of products covered by CBAM has to register on the CBAM register and issue quarterly reports until January 2026. Until this date, every importer will have to apply for authorized declarant status. Starting 2026, imports of CBAM products will need to be made with a CBAM certificate, whose price will be related to the carbon emissions embedded in the products imported, as calculated by the producer/supplier. From 2026, before 31st May of each year, authorized CBAM declarants will issue the CBAM register to submit a CBAM declaration for the previous calendar year.

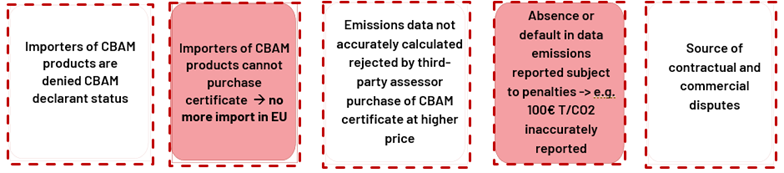

C. Effects of non-compliance

4. EUDR

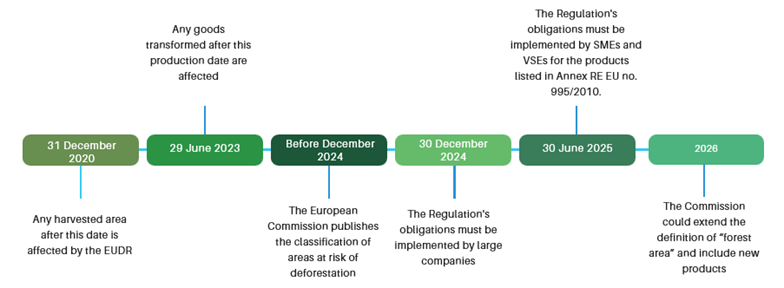

The EUDR aims to tackle global deforestation, a major contributor to climate change and biodiversity loss and imposes strict rules in terms of due diligence to all companies wishing to market affected products in the EU or to export them. The EUDR is part of the EU’s broader strategy to protect biodiversity, as reflected in its commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the European Green Deal. Companies have until 30 December 2024 to be compliant, except for micro and small undertakings for which the EUDR will apply from 30 June 2025.

A. Scope of application

The products concerned by the EUDR are those from the following sectors: cattle, rubber, wood, soya, cocoa, coffee and palm oil. They will only be authorised to be placed on the EU market or exported if they are deforestation-free, produced in accordance with relevant local legislation and covered by a due diligence statement. Any of those product’s export to the EU, found in the food, luxury or automobile industry, in any level of the value chain (not only raw product) are concerned except if they fall into the category of recycled basic and used products that would otherwise be disposed of as waste.

To prevent and dissuade potential deforestation resulting from anticipated acceleration in the activities causing deforestation, any production activity occurring after the 31 December 2020 will be affected. Concerning the transformed goods, this regulation will apply to any products for which the production date is prior to the 29 of June 2023 and 30 December 2024 for wood.

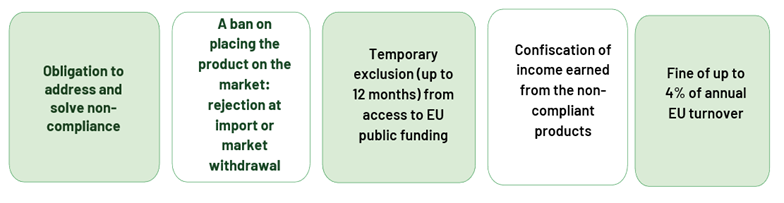

B. Corrective measure and penalties

In case of non-compliance, companies will have to address and solve the non-compliance and may face the following sanctions:

5. Forced Labor regulation

The Forced Labour Regulation aims at preventing products made with forced labor from entering the EU market, prohibiting the import of goods produced using forced labor, requiring companies to ensure their supply chains are free from forced labor and to provide transparency about their sourcing practices, and establishing mechanisms for monitoring and enforcing compliance, including inspections and penalties for violators. The Forced Labour Regulation goal is to combat forced labor globally by leveraging the EU’s market power to encourage ethical labor practices.

A. Scope of application

This regulation will apply to all products entering into the EU market and all parties (economic operator, producer, supplier, importer, etc.) on the supply chain are concerned.

B. Controls and sanctions

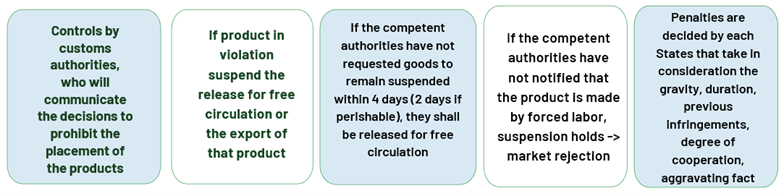

Compliance with the Forced Albor Regulations will be monitored by customs authorities and non-compliance will have the following consequences:

This new EU sustainability reporting landscape is part of a broader effort to promote sustainable development and address global environmental challenges, including in Asia. For several years, Asia has been undergoing significant developments: many nations have implemented their own environmental regulations, reflecting varying levels of commitment and approaches to sustainability.

But how is Asia EU-ESG ready and how will the EU regulations impact companies in China, Indonesia, India, Vietnam and India?

China

Indonesia stands at a crucial juncture where rapid economic development cannot overlook the imperatives of environmental sustainability and social responsibility. Indonesian regulation regarding ESG reflects Indonesia’s commitment to align its business and industrial practices with international standards, while addressing specific local challenges.

Originally a moral concept, Indonesia introduced CSR into its positive law in 2007 through Article 74 of Law No. 40 of 2007 on Limited Liability Companies and Article 15(b) of Law 25/2007 on Capital Investment. These laws served as the basis for other national, provincial, and regional frameworks for CSR, detailing required CSR activities.

CSR is thus framed by a series of laws and policies that encourage companies to integrate responsible practices into their operations. Deforestation, a critical issue in Indonesia due to its vast forest resources, is addressed by strict laws and moratoriums aimed at protecting forests and peatlands. Concurrently, forced labor is combated through a combination of national laws and international conventions, ensuring the protection of workers’ rights.

This detailed overview explores how Indonesia addresses these crucial aspects of regulation, highlighting the laws, policies, and initiatives in place to promote sustainable and responsible growth and the impact of European regulations.

ESG Regulatory Framework in Indonesia

1. Environment

Article 28H(1) of the Indonesian Constitution of 1945 affirms the right of every person to a healthy environment, forming the basis of the legal framework for environmental matters.

Building on this principle, Indonesia’s national development plans and policies, such as the Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), emphasize sustainability as a crucial element of the country’s development strategy. Indonesia’s commitment to international agreements, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement, 2015, also illustrates its dedication to forest conservation and climate change mitigation formalized, among others, through the ambitious Forest and Land Use (FOLU) Net Sink 2030 plan, which foresees that Indonesian forest management will no longer contribute to greenhouse gas emissions by the end of the decade.

In addition to these plans, a body of laws on environmental protection requires companies to mitigate their environmental impact (deforestation, pollution, biodiversity impact, etc.) and contribute to conservation efforts.

Among these laws:

- Law No. 41/1999 on Forestry defines forest areas, regulates forest management, and establishes protection measures, including sanctions for illegal logging and deforestation. This law is crucial for preserving forest resources and promoting sustainable forest practices.

- Law No. 18/2013 on the Prevention and Eradication of Forest Destruction strengthens the enforcement of the 1999 law by providing additional legal certainty and defining sanctions for individuals involved in forest destruction.

- Law No. 32/2009 on Environmental Protection and Management Law establishes principles of environmental protection, including measures to prevent and control environmental degradation, which encompasses deforestation.

Regulation against deforestation in Indonesia, although ambitious on paper, has many shortcomings. A 2011 moratorium on the conversion of primary forests and peatlands, for example, was widely hailed as a major step forward. However, its effectiveness is limited by multiple exceptions and a lack of rigorous monitoring and enforcement. Companies being able to circumvent the rules through concessions, which excludes some of the ambit of the regulations.

Despite the implementation of the Redd+ Program, the expected results are far from being achieved. The program relies on financial incentives for conservation, but the actual impact on the ground is hindered by governance and transparency issues. Funds intended for forest protection are often mismanaged, and local communities, who should be the primary beneficiaries, do not always receive the necessary support for sustainable alternatives to deforestation.

Economic pressure also exerts a considerable influence on deforestation. The palm oil and timber industries represent a major source of revenue for the country. As a result, the government often finds itself in a delicate position, balancing the need to preserve forests with economic growth. This tension results in inconsistent policies and a lack of political will to address the root causes of deforestation.

Civil society and NGO initiatives also face many obstacles. Environmental groups often face opposition from businesses and, sometimes, direct threats to their security. Moreover, despite efforts such as RSPO certifications, these voluntary initiatives sometimes lack rigor and transparency.

While Indonesia has taken significant steps to regulate deforestation, truly effective conservation efforts would require significant investments to ensure a rigorous law enforcement, and increased collaboration with local communities.

2. Social

Indonesian labor law promotes responsible business practices by ensuring fair wages, safe working conditions, and development opportunities for employees. These laws indirectly support CSR principles by fostering a fair and just work environment.

Indonesia has also established a comprehensive legal framework to combat forced labor, aligned with international standards. The Indonesian Constitution provides fundamental principles regarding human rights and labor rights. Article 28(D) guarantees every citizen the right to work and receive fair wages and fair treatment, forming the constitutional basis against forced labor. Indonesia has ratified various international conventions on forced labor, including the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention on Forced Labour of 1930 (No. 29) and the Convention on the Abolition of Forced Labour of 1957 (No. 105).

Indonesia has developed a National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights, which includes measures to address human rights violations in business operations, including forced labor. The plan emphasizes corporate responsibility to respect human rights throughout their operations.

This commitment to combating forced labor is translated into positive law: Law No. 13/2003 on Manpower expressly prohibits forced labor. Some provisions of the Indonesian Penal Code (KUHP) address forced labor through articles on human trafficking, slavery, and exploitation. These provisions provide for criminal penalties for individuals and entities engaged in forced labor practices, providing a legal basis for prosecuting such offenses.

Various government agencies, including the Ministry of Manpower, the National Police, and the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM), are responsible for enforcing labor laws and regulations. These agencies investigate complaints of forced labor and ensure compliance with legal standards, providing oversight and accountability.

However, combating forced labor remains a challenge for the government. Companies often enjoy relative impunity due to poor law enforcement. Some actors exploit the vulnerabilities of the poorest and least educated populations, trapping them in forced labor conditions. Migrant workers are particularly at risk, often having few legal recourses and fearing retaliation or deportation if they report their working conditions.

The efforts of civil society and NGOs to combat forced labor are essential but insufficient given the scale of the problem. These organizations play a crucial role in awareness-raising, victim assistance, and advocacy for stricter policies. However, they face significant challenges, such as lack of funding, opposition from businesses, and, in some cases, threats to their security.

3. Governance

Regulation No. 47 of 2012 on Social and Environmental Responsibilities of Limited Liability Companies specifies CSR principles applicable to companies in the natural resources sector, laid out by the 2007 laws, making the board of directors responsible for CSR implementation and requiring the preparation of an annual CSR operations plan (and reporting), including an annual CSR budget, based on the company’s financial capacity. However, all other private companies are only required to include information on the implementation of their social and environmental responsibility programs in their annual report.

Article 66 of Law No. 40 of 2007 also provides for companies operating in the natural resources sector to have certain annual reporting obligations, particularly regarding measures implemented by the company in terms of ESG. This report relates to TJSL (Tanggung Jawab Sosial dan Lingkungan) obligations, which can be understood as the company’s commitments to CSR, not just environmental.

However, the implementation of these obligations by Indonesian companies is limited. According to a survey by the Foundation for International Human Rights Reporting Standards (FIHRRST) and Moores Rowland Indonesia from 2020, only 16% of public company reports mention TJSL obligations.

Since 30th April 2022, publicly listed companies have been required to prepare and submit a Sustainability Report annually to the Indonesia Financial Service Authority (OJK) which is made accessible to the public. This report must mention a list of organizations and associations related to the implementation of fair finance, as well as the following information:

- Sustainable strategy;

- Summary of the company’s sustainability efforts (economic, social, and environmental);

- Brief introduction of the listed company;

- Board remarks;

- Governance of sustainable actions;

- Performance of sustainable actions implemented;

- Written verification by independent parties, if any;

- Reader feedback, if any; and

- Response to feedback from the previous year’s report.

In accordance with Article 13 of POJK.03/2017, in case of non-compliance with this obligation, companies may be subject to administrative sanctions such as reprimand, censure, or written warning.

Reception of EU Regulation in Indonesia

Indonesia is currently negotiating with the European Union regarding the implementation of the CBAM, facing challenges and tensions. There have been significant debates and negative press surrounding this issue, highlighting the complexities and potential impacts on trade relations between the European Union and Indonesia. Negotiations are ongoing, with both parties seeking to strike a balance between environmental objectives and economic interests. The implementation of CBAM could have significant implications for Indonesian exports to the EU, especially in carbon-intensive sectors.

A Joint Task Force has also been implemented between Indonesia, Malaysia, and the European Union for the implementation of the deforestation regulation. The aim of this joint working group is to support the two Southeast Asian countries, particularly sensitive to deforestation issues, and their local companies in adapting to the new obligations posed by the new regulation.

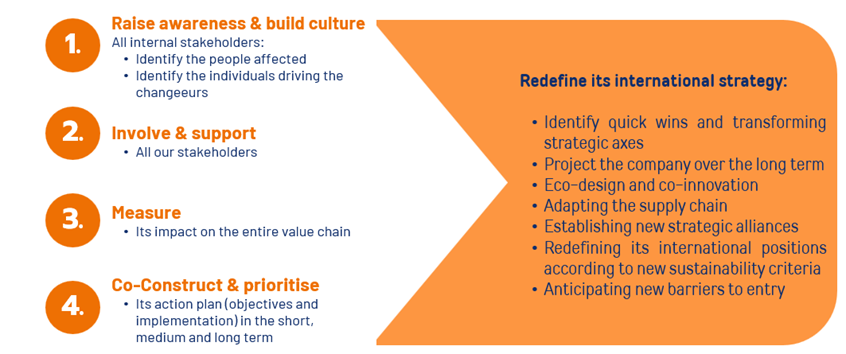

Impact of EU regulations on companies in Asia

The implementation of ESG principles and compliance with regulations can have a significant impact on companies operating in or trading with the EU. Companies must adapt to new standards and practices to maintain market access and competitiveness. This includes integrating sustainability goals into their operations, investing in cleaner technologies, and ensuring compliance with environmental and social regulations.

The CSRD will require subsidiaries of European companies or companies within the value chain of European partners to initiate data collection and sustainability report compilation to provide to their European partners or parent companies upon request.

Subsidiaries of European companies will benefit from available resources and a sustainability strategy that has been cascaded from the parent company whereas companies within the value chain of European businesses will need to carry out more preparatory work to meet requirements from their European partners to comply with the CSRD as they may lack guidance on European regulations. It is therefore paramount that companies educate themselves and seek guidance from their European partners to assess actions to be taken at their level to initiate data collection and sustainability report compilation.

Although the implementation of the CBAM by the EU directly impacts key industries, exporters must navigate the evolving scope of CBAM, which may expand to include indirect emissions and additional carbon-intensive sectors. To remain competitive in the EU and minimize the impact on production and export activities, exporters are urged to monitor CBAM progress closely, study reporting requirements for greenhouse gas emissions, assess financial implications, evaluate commercial opportunities for greener products, and implement decarbonization policies and greener production methods.

In addition to CBAM, exporters must comply with EU regulations on forced labor and deforestation to access the European market. The forced labor products ban requires rigorous due diligence to ensure no forced labor risks exist in the supply chain, including online sales. Similarly, exporters must provide evidence that their products have not contributed to deforestation or forest degradation. Exporters face the challenge of increased effort in tracking and tracing the origins of export goods, requiring training for all participants in the supply chain.

Companies that succeed in adapting to these changes can enhance their reputation and competitiveness in the global market. However, those that do not comply may face barriers to market entry and potential financial sanctions. The emphasis on sustainability and responsible business practices should drive innovation and create new opportunities for proactive companies facing environmental and social challenges.