Exploring the impact of the EU sustainability reporting landscape on companies in Asia

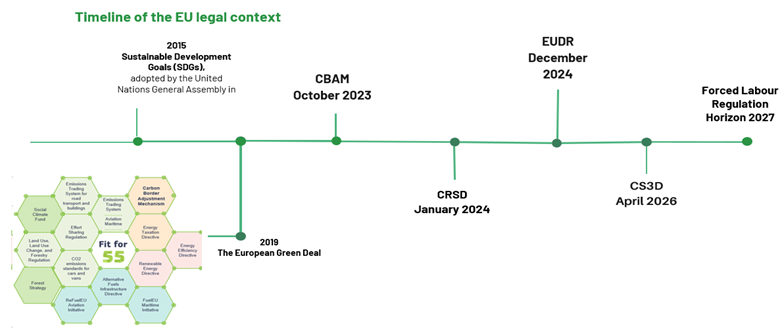

The European Union (“EU”) has been a driving force in environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) regulations. The EU’s environmental policies are part of a broader commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals (“SDGs”), adopted by the United Nations General Assembly[1] in 2015. These goals address critical global challenges such as climate change, environmental degradation, and social inequality.

In 2019, the EU announced the European Green Deal, setting an ambitious target of achieving zero net greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions by 2050. This initiative underscores the EU’s dedication to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent.

To support this goal, the EU has implemented a series of regulatory measures designed to promote sustainability and mitigate the impacts of climate change, including:

- the Directive 2022/2464 on corporate sustainability reporting (“CRSD”),

- the Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 on the making available on the Union market and the export from the Union of certain commodities and products associated with deforestation and forest degradation (“EUDR”),

- the Regulation (EU) 2023/956 establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism (“CBAM”),

- the proposed Regulation (EU) on prohibiting products made with forced labour on the Union market (“Forced Labor Regulation”).

Together, these initiatives seek to drive a more sustainable economy by ensuring that companies adhere to stringent environmental standards and provide clear, reliable information to investors and consumers.

While these regulations are EU-driven, their impact extends globally. Companies worldwide that wish to do business in the EU or with EU-based companies must adapt to these standards. This requirement to adopt the EU standards has a cascading effect, pushing global supply chains towards greater sustainability and ethical practices.

The ASEAN Taxonomy Board (“ATB”), set up under the auspices of the ASEAN Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meeting also participates to the creation of ESG guidelines by developing, maintaining and promoting a multi-tiered guide on ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance (“ASEAN Taxonomy”) which identifies economic activities that are sustainable and help direct investment and funding towards a sustainable ASEAN.

The ASEAN Taxonomy (Version 3 published on 27 March 2024) is an overarching guide for all ASEAN Member States (“AMS”), complementing their respective national sustainability initiatives and serving as ASEAN’s common language for sustainable finance. It is designed to ensure that AMS have a framework that suits their economic and social structures that other frameworks may not be able to address.

In this newsletter, we aim to provide:

- a better understanding of the EU’s sustainability reporting landscape;

- how it compares to five key Asian jurisdictions: China, Indonesia, India, Vietnam and Singapore; and

- steps to take to comply with the new EU regulations.

I. Understanding the EU’s sustainability reporting landscape

1. Key definitions and timeline

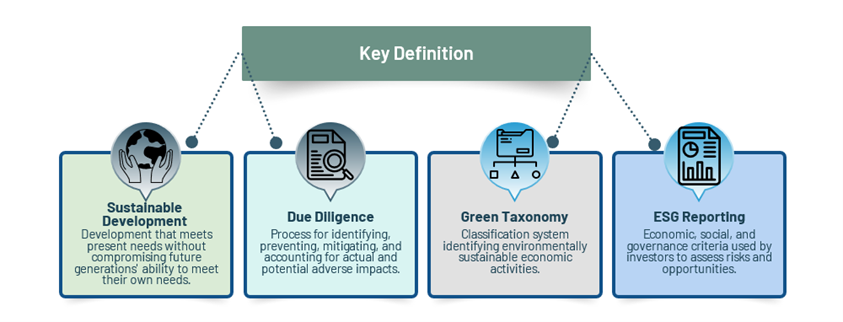

A. Key Definitions

2. Timeline of the EU legal context

3. CSRD

The CSRD is a critical part of the EU’s environmental strategy. It replaces Directive 2014/95 on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups (“NFRD”) and aims to enhance the reliability and accessibility of sustainability information through standardized and comprehensive reporting. Since 1st January 2024, the CSRD mandates companies that meet certain thresholds to report on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, integrating sustainable finance and green taxonomy principles. It introduces the concept of “dual materiality,” ensuring that companies report on how sustainability issues affect them and their impact on society and the environment. This standardized reporting aims to improve the reliability and transparency of sustainability data, guiding investors, and stakeholders towards more informed decisions.

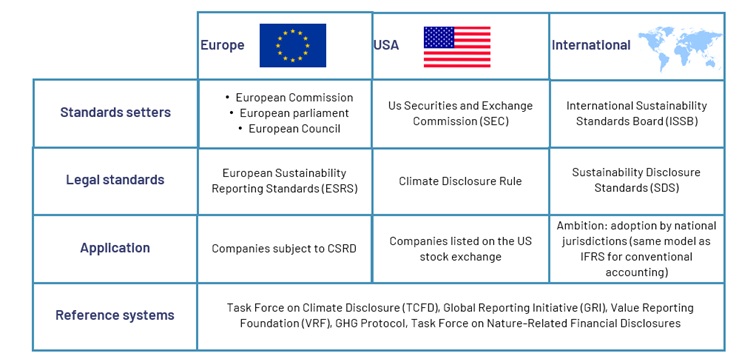

A. Comparison with other international initiatives

In comparison with the other international regulations, the CSRD can be considered as the most ambitious of the ESG information standardisation initiatives.

B. Scope of application and road map

CSRD will be implemented in phases as illustrated below:

| Large Public Interest Entities (PIEs) with >500 Employees (Already Subject to NFRD): | Large Companies Newly Subject to CSRD (Including Large Listed Companies with < 500 Employees): | Listed Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): | Non-European Companies Meeting CSRD Conditions: |

| 2024 – Immediate Action: Begin preparing for CSRD compliance based on cross-sector standards. | 2024/2025 – Preparation Phase: Prepare for CSRD compliance based on cross-sector standards. | 2026/2028 – Preparation and Transition Phase : Prepare for CSRD compliance based on specific ESRS standards. | 2028-Preparation Phase : Prepare for CSRD compliance based on specific ESRS standards. |

| Key Steps: Assess current sustainability reporting and identify gaps.Update internal processes for data collection and reporting.Allocate resources and designate teams for CSRD compliance.Engage with stakeholders to understand their expectations.Conduct a materiality analysis to identify key sustainability issues. Outcomes: Establish a CSRD compliance framework.Initiate data gathering and reporting activities. | Key Steps: Familiarize with CSRD requirements and guidelines.Conduct a gap analysis comparing current practices with CSRD requirements.Develop a roadmap and timeline for CSRD implementation.Enhance internal capacity for sustainability reporting.Consider engaging external experts for support. Outcomes: Gain a clear understanding of CSRD obligations.Begin internal preparations for compliance. | Key Steps: Monitor developments in ESRS standards and guidelines.Evaluate readiness for sustainability reporting.Implement changes to internal processes and systems.Train and support relevant staff members.Develop a communication strategy for stakeholder engagement. Outcomes: Align internal systems with CSRD requirements.Begin sustainability reporting activities | Key Steps: Understand CSRD requirements and implications for non-European companies.Assess operations and supply chains comprehensively.Collaborate with European subsidiaries or partners for data gathering.Develop strategies to address compliance challenges.Establish communication channels with regulatory authorities for guidance. Outcomes: Develop a CSRD compliance plan.Initiate necessary actions to meet requirements. |

C. Controls and penalties:

Statutory auditor or audit form must carry out the assurance of sustainability reporting. As most of the European regulations, each member state must ensure that the provisions of the directive are implemented by providing an effective, proportionate, and dissuasive sanction to auditors and audit firms.

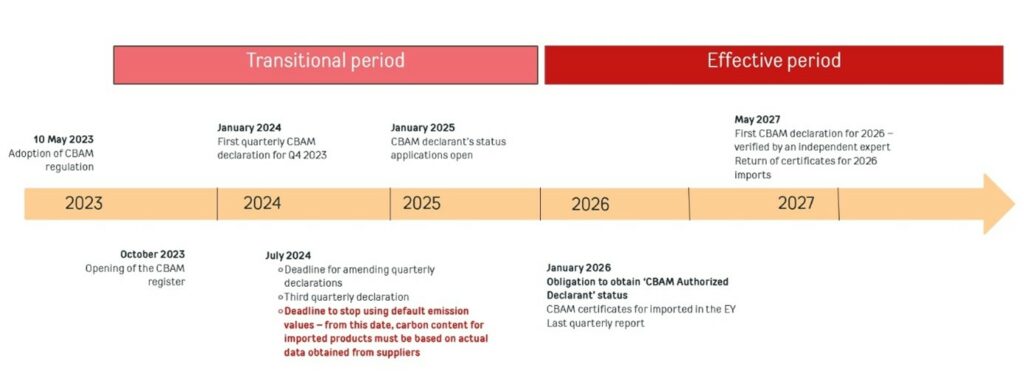

3. CBAM

The CBAM aims to prevent carbon leakage by ensuring equivalent carbon pricing for imports and EU products. It gradually phases out free allowances under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) and introduces a carbon pricing mechanism for imports, ensuring that non-EU products are not favored over EU products. This mechanism supports the goal of climate neutrality and aligns with international climate commitments, such as the Glasgow Climate Pact and the Paris Agreement. These regulations aim to reduce the EU’s carbon footprint and promote sustainable economic activities that do not exacerbate climate change.

A. Scope of application:

The CBAM creates new regulatory obligations for importers and will initially apply only to the following sectors: cement, aluminum, nitrogen fertilizers, electricity and hydrogen.

The CBAM places the main liability on the EU importer, however the regulatory obligations will require concerns all economic operators and strong cooperation between producers or suppliers and buyers involved in the supply chain concerned in international trade from or to of products imported in the EU. The CBAM provides a transition phase and an effective operating period:

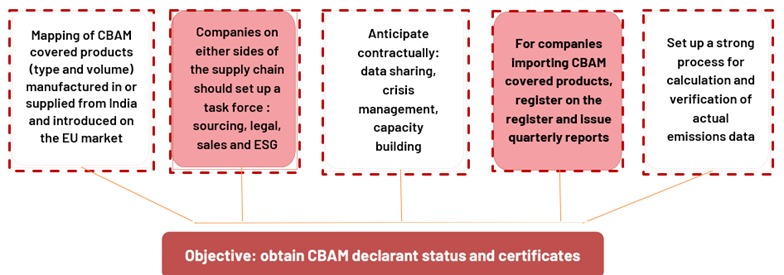

B. Obligations under CBAM

First, every importer of products covered by CBAM has to register on the CBAM register and issue quarterly reports until January 2026. Until this date, every importer will have to apply for authorized declarant status. Starting 2026, imports of CBAM products will need to be made with a CBAM certificate, whose price will be related to the carbon emissions embedded in the products imported, as calculated by the producer/supplier. From 2026, before 31st May of each year, authorized CBAM declarants will issue the CBAM register to submit a CBAM declaration for the previous calendar year.

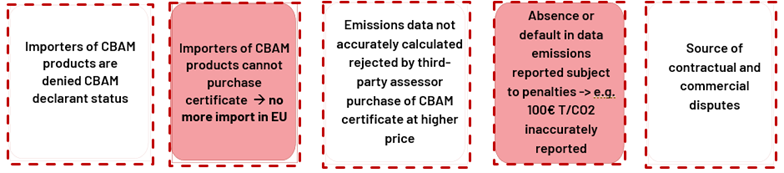

C. Effects of non-compliance

4. EUDR

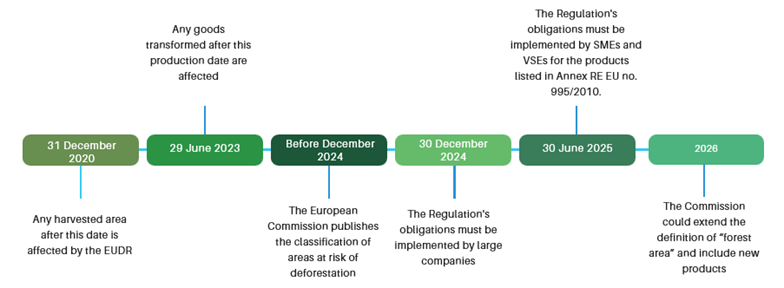

The EUDR aims to tackle global deforestation, a major contributor to climate change and biodiversity loss and imposes strict rules in terms of due diligence to all companies wishing to market affected products in the EU or to export them. The EUDR is part of the EU’s broader strategy to protect biodiversity, as reflected in its commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the European Green Deal. Companies have until 30 December 2024 to be compliant, except for micro and small undertakings for which the EUDR will apply from 30 June 2025.

A. Scope of application

The products concerned by the EUDR are those from the following sectors: cattle, rubber, wood, soya, cocoa, coffee and palm oil. They will only be authorised to be placed on the EU market or exported if they are deforestation-free, produced in accordance with relevant local legislation and covered by a due diligence statement. Any of those product’s export to the EU, found in the food, luxury or automobile industry, in any level of the value chain (not only raw product) are concerned except if they fall into the category of recycled basic and used products that would otherwise be disposed of as waste.

To prevent and dissuade potential deforestation resulting from anticipated acceleration in the activities causing deforestation, any production activity occurring after the 31 December 2020 will be affected. Concerning the transformed goods, this regulation will apply to any products for which the production date is prior to the 29 of June 2023 and 30 December 2024 for wood.

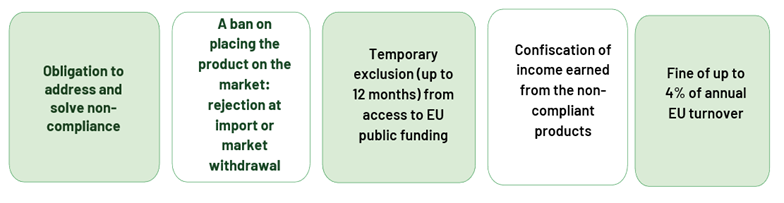

B. Corrective measure and penalties

In case of non-compliance, companies will have to address and solve the non-compliance and may face the following sanctions:

5. Forced Labor regulation

The Forced Labour Regulation aims at preventing products made with forced labor from entering the EU market, prohibiting the import of goods produced using forced labor, requiring companies to ensure their supply chains are free from forced labor and to provide transparency about their sourcing practices, and establishing mechanisms for monitoring and enforcing compliance, including inspections and penalties for violators. The Forced Labour Regulation goal is to combat forced labor globally by leveraging the EU’s market power to encourage ethical labor practices.

A. Scope of application

This regulation will apply to all products entering into the EU market and all parties (economic operator, producer, supplier, importer, etc.) on the supply chain are concerned.

B. Controls and sanctions

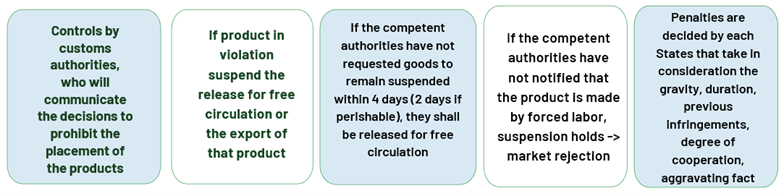

Compliance with the Forced Albor Regulations will be monitored by customs authorities and non-compliance will have the following consequences:

This new EU sustainability reporting landscape is part of a broader effort to promote sustainable development and address global environmental challenges, including in Asia. For several years, Asia has been undergoing significant developments: many nations have implemented their own environmental regulations, reflecting varying levels of commitment and approaches to sustainability.

But how is Asia EU-ESG ready and how will the EU regulations impact companies in China, Indonesia, India, Vietnam and India?

Singapore

In Singapore, ESG obligations have emerged as a central element of government policy and corporate governance. As sustainability and social responsibility issues gain global significance, Singapore has taken proactive steps to integrate these considerations into its regulatory and financial framework. In response to challenges such as climate change, social diversity, and corporate transparency, Singapore has implemented a series of regulations, initiatives, and guidelines aimed at promoting robust ESG practices and enhancing the resilience of its economy.

ESG Regulatory Framework in Singapore

1. Environment: Singapore Green Plan 20230

Due to its geographical location and climate challenges, Singapore is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, such as rising sea levels, flooding, and heatwaves. Despite being considered Asia’s most sustainable city and the world’s 4th, Singapore faces issues such as excessive use of disposable plastics, coupled with a low plastic waste recycling rate (6%), posing a significant environmental problem, and widespread use of air conditioning, accounting for 20% of Singapore’s carbon emissions.

To address these challenges, Singapore has embarked on an ambitious initiative to enhance environmental sustainability and combat climate change. Crystalized in the Singapore Green Plan, Singapore has set ambitious and concrete goals for the next 6 years, strengthening its commitments under the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030 and the Paris Agreement 2015, reflecting its aspiration to achieve long-term net-zero emissions by 2050. The Green Plan is built on five pillars:

- City in nature: creating a green, livable, and sustainable home for Singaporeans.

- Sustainable living: making carbon emission reduction, environmental preservation, and resource and energy economy a way of life in Singapore.

- Energy reset: using cleaner energies and increasing energy efficiency to reduce Singapore’s carbon footprint.

- Green economy: seeking green growth opportunities to create new jobs, transform Singapore’s industries, and make sustainability a competitive advantage.

- Resilient future: strengthening Singapore’s climate resilience and improving its food security.

To achieve these goals, the Green Plan outlines a series of actions, such as increasing energy production from renewable sources, promoting sustainable transportation modes, waste reduction, and improving the energy efficiency of buildings. To contribute to the realization of the five key pillars, the government has introduced a series of new initiatives and objectives such as the Research, Innovation and Enterprise 2025 Plan aimed at promoting local innovation and encouraging businesses to anchor their R&D activities in Singapore to develop new sustainable development solutions.

A. Environmental Protection and Management Act

Singapore’s Environmental Protection and Management Act 1999 (“EPMA”) represents a fundamental pillar of Singapore’s environmental legislation. As an essential regulatory framework, the EPMA sets rigorous standards for environmental protection and natural resource management. Its scope includes regulating and controlling activities that may cause harm to the environment, such as air, water, and soil pollution. This legislation also provides guidelines for preventing, controlling, and mitigating environmental pollution, as well as promoting sustainable use of natural resources.

One of the strengths of the EPMA lies in its ability to promote environmental responsibility at all levels of society. By encouraging businesses, citizens, and government agencies to be aware of environmental issues, the EPMA fosters a culture of proactive environmental management. By imposing sanctions on offenders and encouraging cooperation among different actors, this law ensures effective and equitable enforcement of environmental regulations.

B. Energy Conservation Act

Singapore’s Energy Conservation Act 2012 (“ECA”) represents a fundamental law in the country’s efforts to promote energy conservation and reduce its reliance on fossil fuels. This legislation is of paramount importance in the country’s national strategy.

One of the main obligations imposed by the ECA is to establish standards and guidelines for energy management in various sectors of the economy. This includes implementing programs to improve energy efficiency in buildings, industrial facilities, and equipment, as well as promoting eco-energy technologies and practices.

C. Singapore-Asia taxonomy

Launched by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (“MAS”) in December 2023, the Singapore-Asia taxonomy is a guidance framework that will benefit businesses and financial institutions that adopt it, helping them better manage climate risks and guiding them towards achieving “net zero.” The framework provides detailed thresholds and criteria for defining green and transition activities in eight key sectors, which represent 90% of Asia’s greenhouse gas emissions. The taxonomy’s sophisticated traffic light classification system, the first of its kind globally, identifies activities as green (sustainable), orange (transitional), or red (ineligible) across various sectors[1]. This taxonomy is aligned with the 5 pillars of the Green Plan 2030.

2. Social

The social aspects of Singapore’s ESG policy are primarily addressed by two laws: the Workplace Safety and Health Act 2006 and the Employment Act 1968.

According to an article by Ivan Tan Ren Yi[1], companies listed in Singapore, while among the top-ranked in Asia for ESG, surprisingly rank among the lowest when rankings are adjusted to only consider environmental and social factors compared to companies in other highly developed Asian economies such as Hong Kong, Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. For the author, while this reflects Singapore’s long-standing reputation for good corporate governance, it also shows that, comparatively, environmental and social factors are insufficient.

3. Governance

A. MAS Directives

MAS directives play a crucial role in managing ESG obligations in the financial sector. By encouraging financial institutions to integrate ESG considerations into their policies, decision-making processes, and business practices, MAS promotes a holistic approach to social and environmental responsibility. This goes beyond mere regulatory compliance to encourage companies to adopt sustainable business practices and positively contribute to society.

B. Corporate Governance Code

Singapore’s Corporate Governance Code (last version issued on 11 January 2023) represents a key pillar of corporate governance in the country, aiming to promote strong and transparent practices among listed companies. By encouraging companies to adopt governance practices that promote transparency, accountability, and protection of shareholders’ and stakeholders’ interests, the code sets standards for ethical and responsible business conduct.

One of the strengths of the Corporate Governance Code lies in its commitment to fostering a diverse and competent composition of boards of directors. By emphasizing diversity and competence, the code aims to ensure effective governance and strengthen investor confidence in listed companies. Furthermore, by promoting transparent disclosure of both financial and non-financial information, including policies, processes, and performance regarding social and environmental responsibility, the code enhances transparency and accountability in managing ESG issues.

C. CRD Reporting

On 28th February 2024 Singapore announced the implementation of climate reporting obligations for listed companies and large unlisted companies, following the IFRS standards of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). Like in Europe, these measures will be gradually implemented starting from 2025.

D. Singapore Green Finance Centre (SGFC)

The SGFC is a key initiative in Singapore’s strategy to become a sustainable financial hub and promote green finance in the region. This center aims to mobilize capital towards sustainable investments by facilitating the development of green financial products, providing advice and training on sustainable finance, and encouraging collaboration among financial actors, businesses, and public authorities.

Impact of EU regulations on companies in Asia

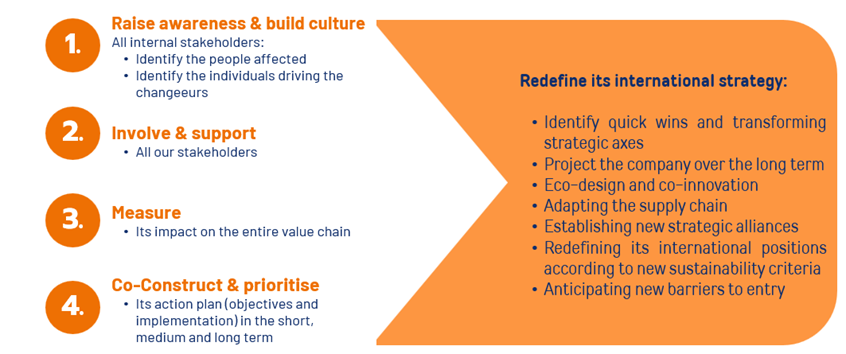

The implementation of ESG principles and compliance with regulations can have a significant impact on companies operating in or trading with the EU. Companies must adapt to new standards and practices to maintain market access and competitiveness. This includes integrating sustainability goals into their operations, investing in cleaner technologies, and ensuring compliance with environmental and social regulations.

The CSRD will require subsidiaries of European companies or companies within the value chain of European partners to initiate data collection and sustainability report compilation to provide to their European partners or parent companies upon request.

Subsidiaries of European companies will benefit from available resources and a sustainability strategy that has been cascaded from the parent company whereas companies within the value chain of European businesses will need to carry out more preparatory work to meet requirements from their European partners to comply with the CSRD as they may lack guidance on European regulations. It is therefore paramount that companies educate themselves and seek guidance from their European partners to assess actions to be taken at their level to initiate data collection and sustainability report compilation.

Although the implementation of the CBAM by the EU directly impacts key industries, exporters must navigate the evolving scope of CBAM, which may expand to include indirect emissions and additional carbon-intensive sectors. To remain competitive in the EU and minimize the impact on production and export activities, exporters are urged to monitor CBAM progress closely, study reporting requirements for greenhouse gas emissions, assess financial implications, evaluate commercial opportunities for greener products, and implement decarbonization policies and greener production methods.

In addition to CBAM, exporters must comply with EU regulations on forced labor and deforestation to access the European market. The forced labor products ban requires rigorous due diligence to ensure no forced labor risks exist in the supply chain, including online sales. Similarly, exporters must provide evidence that their products have not contributed to deforestation or forest degradation. Exporters face the challenge of increased effort in tracking and tracing the origins of export goods, requiring training for all participants in the supply chain.

Companies that succeed in adapting to these changes can enhance their reputation and competitiveness in the global market. However, those that do not comply may face barriers to market entry and potential financial sanctions. The emphasis on sustainability and responsible business practices should drive innovation and create new opportunities for proactive companies facing environmental and social challenges.

[3] Energy, real estate, transport, agriculture and forestry/land use, industry, information and communication technologies, waste and carbon capture and sequestration

[4] https://www.singaporelawreview.com/juris-illuminae-entries/2020/the-future-of-esg-in-singapore