Exploring the impact of the EU sustainability reporting landscape on companies in Asia

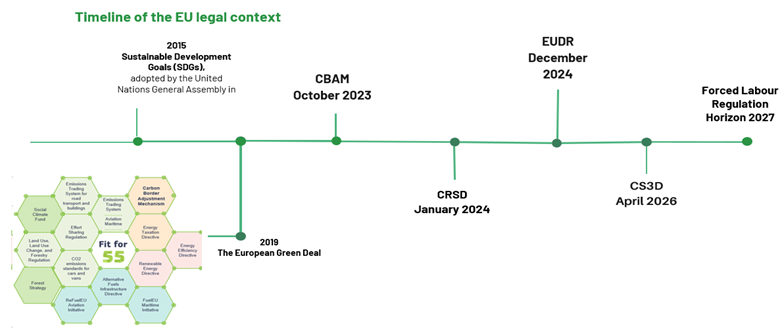

The European Union (“EU”) has been a driving force in environmental, social and governance (“ESG”) regulations. The EU’s environmental policies are part of a broader commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals (“SDGs”), adopted by the United Nations General Assembly[1] in 2015. These goals address critical global challenges such as climate change, environmental degradation, and social inequality.

In 2019, the EU announced the European Green Deal, setting an ambitious target of achieving zero net greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions by 2050. This initiative underscores the EU’s dedication to becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent.

To support this goal, the EU has implemented a series of regulatory measures designed to promote sustainability and mitigate the impacts of climate change, including:

- the Directive 2022/2464 on corporate sustainability reporting (“CRSD”),

- the Regulation (EU) 2023/1115 on the making available on the Union market and the export from the Union of certain commodities and products associated with deforestation and forest degradation (“EUDR”),

- the Regulation (EU) 2023/956 establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism (“CBAM”),

- the proposed Regulation (EU) on prohibiting products made with forced labour on the Union market (“Forced Labor Regulation”).

Together, these initiatives seek to drive a more sustainable economy by ensuring that companies adhere to stringent environmental standards and provide clear, reliable information to investors and consumers.

While these regulations are EU-driven, their impact extends globally. Companies worldwide that wish to do business in the EU or with EU-based companies must adapt to these standards. This requirement to adopt the EU standards has a cascading effect, pushing global supply chains towards greater sustainability and ethical practices.

The ASEAN Taxonomy Board (“ATB”), set up under the auspices of the ASEAN Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meeting also participates to the creation of ESG guidelines by developing, maintaining and promoting a multi-tiered guide on ASEAN Taxonomy for Sustainable Finance (“ASEAN Taxonomy”) which identifies economic activities that are sustainable and help direct investment and funding towards a sustainable ASEAN.

The ASEAN Taxonomy (Version 3 published on 27 March 2024) is an overarching guide for all ASEAN Member States (“AMS”), complementing their respective national sustainability initiatives and serving as ASEAN’s common language for sustainable finance. It is designed to ensure that AMS have a framework that suits their economic and social structures that other frameworks may not be able to address.

In this newsletter, we aim to provide:

- a better understanding of the EU’s sustainability reporting landscape;

- how it compares to five key Asian jurisdictions: China, Indonesia, India, Vietnam and Singapore; and

- steps to take to comply with the new EU regulations.

I. Understanding the EU’s sustainability reporting landscape

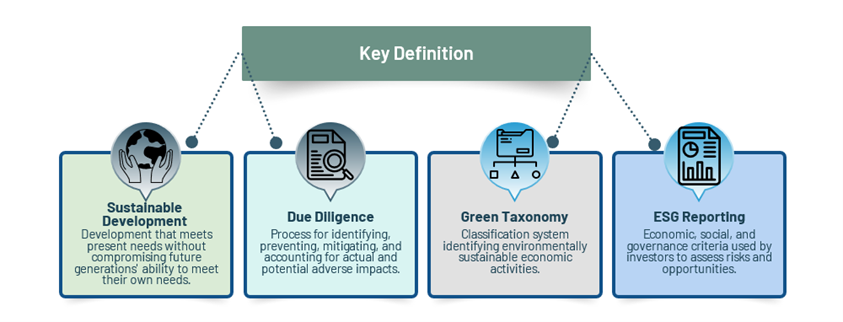

1. Key definitions and timeline

A. Key Definitions

2. Timeline of the EU legal context

3. CSRD

The CSRD is a critical part of the EU’s environmental strategy. It replaces Directive 2014/95 on disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups (“NFRD”) and aims to enhance the reliability and accessibility of sustainability information through standardized and comprehensive reporting. Since 1st January 2024, the CSRD mandates companies that meet certain thresholds to report on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, integrating sustainable finance and green taxonomy principles. It introduces the concept of “dual materiality,” ensuring that companies report on how sustainability issues affect them and their impact on society and the environment. This standardized reporting aims to improve the reliability and transparency of sustainability data, guiding investors, and stakeholders towards more informed decisions.

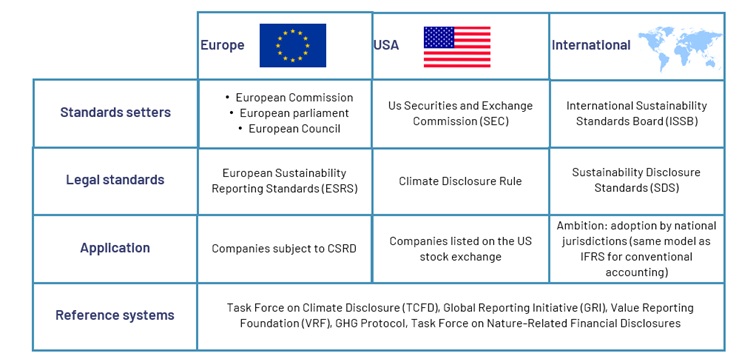

A. Comparison with other international initiatives

In comparison with the other international regulations, the CSRD can be considered as the most ambitious of the ESG information standardisation initiatives.

B. Scope of application and road map

CSRD will be implemented in phases as illustrated below:

| Large Public Interest Entities (PIEs) with >500 Employees (Already Subject to NFRD): | Large Companies Newly Subject to CSRD (Including Large Listed Companies with < 500 Employees): | Listed Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): | Non-European Companies Meeting CSRD Conditions: |

| 2024 – Immediate Action: Begin preparing for CSRD compliance based on cross-sector standards. | 2024/2025 – Preparation Phase: Prepare for CSRD compliance based on cross-sector standards. | 2026/2028 – Preparation and Transition Phase : Prepare for CSRD compliance based on specific ESRS standards. | 2028-Preparation Phase : Prepare for CSRD compliance based on specific ESRS standards. |

| Key Steps: Assess current sustainability reporting and identify gaps.Update internal processes for data collection and reporting.Allocate resources and designate teams for CSRD compliance.Engage with stakeholders to understand their expectations.Conduct a materiality analysis to identify key sustainability issues. Outcomes: Establish a CSRD compliance framework.Initiate data gathering and reporting activities. | Key Steps: Familiarize with CSRD requirements and guidelines.Conduct a gap analysis comparing current practices with CSRD requirements.Develop a roadmap and timeline for CSRD implementation.Enhance internal capacity for sustainability reporting.Consider engaging external experts for support. Outcomes: Gain a clear understanding of CSRD obligations.Begin internal preparations for compliance. | Key Steps: Monitor developments in ESRS standards and guidelines.Evaluate readiness for sustainability reporting.Implement changes to internal processes and systems.Train and support relevant staff members.Develop a communication strategy for stakeholder engagement. Outcomes: Align internal systems with CSRD requirements.Begin sustainability reporting activities | Key Steps: Understand CSRD requirements and implications for non-European companies.Assess operations and supply chains comprehensively.Collaborate with European subsidiaries or partners for data gathering.Develop strategies to address compliance challenges.Establish communication channels with regulatory authorities for guidance. Outcomes: Develop a CSRD compliance plan.Initiate necessary actions to meet requirements. |

C. Controls and penalties:

Statutory auditor or audit form must carry out the assurance of sustainability reporting. As most of the European regulations, each member state must ensure that the provisions of the directive are implemented by providing an effective, proportionate, and dissuasive sanction to auditors and audit firms.

3. CBAM

The CBAM aims to prevent carbon leakage by ensuring equivalent carbon pricing for imports and EU products. It gradually phases out free allowances under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) and introduces a carbon pricing mechanism for imports, ensuring that non-EU products are not favored over EU products. This mechanism supports the goal of climate neutrality and aligns with international climate commitments, such as the Glasgow Climate Pact and the Paris Agreement. These regulations aim to reduce the EU’s carbon footprint and promote sustainable economic activities that do not exacerbate climate change.

A. Scope of application:

The CBAM creates new regulatory obligations for importers and will initially apply only to the following sectors: cement, aluminum, nitrogen fertilizers, electricity and hydrogen.

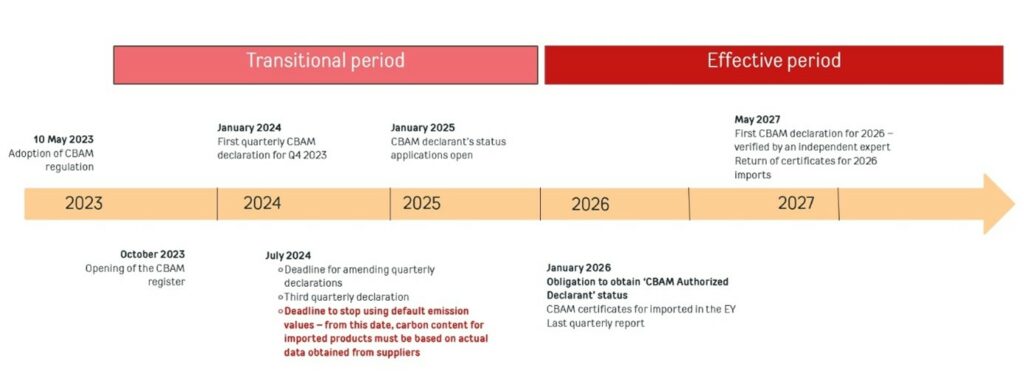

The CBAM places the main liability on the EU importer, however the regulatory obligations will require concerns all economic operators and strong cooperation between producers or suppliers and buyers involved in the supply chain concerned in international trade from or to of products imported in the EU. The CBAM provides a transition phase and an effective operating period:

B. Obligations under CBAM

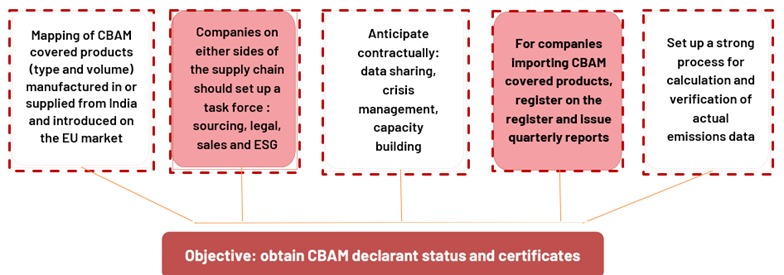

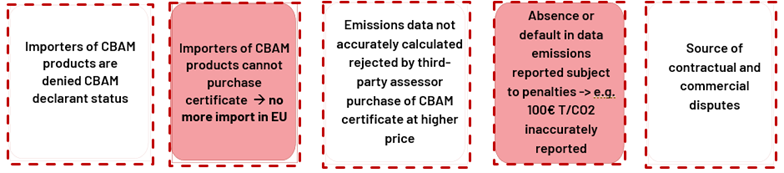

First, every importer of products covered by CBAM has to register on the CBAM register and issue quarterly reports until January 2026. Until this date, every importer will have to apply for authorized declarant status. Starting 2026, imports of CBAM products will need to be made with a CBAM certificate, whose price will be related to the carbon emissions embedded in the products imported, as calculated by the producer/supplier. From 2026, before 31st May of each year, authorized CBAM declarants will issue the CBAM register to submit a CBAM declaration for the previous calendar year.

C. Effects of non-compliance

4. EUDR

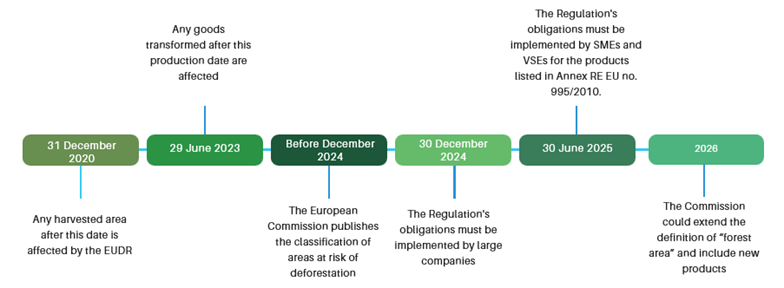

The EUDR aims to tackle global deforestation, a major contributor to climate change and biodiversity loss and imposes strict rules in terms of due diligence to all companies wishing to market affected products in the EU or to export them. The EUDR is part of the EU’s broader strategy to protect biodiversity, as reflected in its commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the European Green Deal. Companies have until 30 December 2024 to be compliant, except for micro and small undertakings for which the EUDR will apply from 30 June 2025.

A. Scope of application

The products concerned by the EUDR are those from the following sectors: cattle, rubber, wood, soya, cocoa, coffee and palm oil. They will only be authorised to be placed on the EU market or exported if they are deforestation-free, produced in accordance with relevant local legislation and covered by a due diligence statement. Any of those product’s export to the EU, found in the food, luxury or automobile industry, in any level of the value chain (not only raw product) are concerned except if they fall into the category of recycled basic and used products that would otherwise be disposed of as waste.

To prevent and dissuade potential deforestation resulting from anticipated acceleration in the activities causing deforestation, any production activity occurring after the 31 December 2020 will be affected. Concerning the transformed goods, this regulation will apply to any products for which the production date is prior to the 29 of June 2023 and 30 December 2024 for wood.

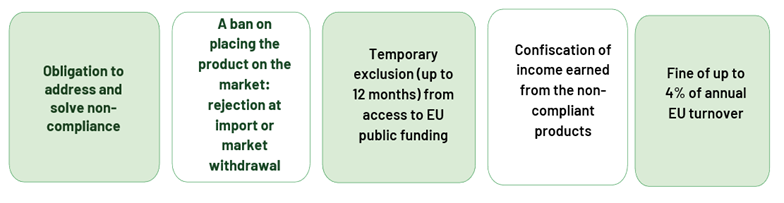

B. Corrective measure and penalties

In case of non-compliance, companies will have to address and solve the non-compliance and may face the following sanctions:

5. Forced Labor regulation

The Forced Labour Regulation aims at preventing products made with forced labor from entering the EU market, prohibiting the import of goods produced using forced labor, requiring companies to ensure their supply chains are free from forced labor and to provide transparency about their sourcing practices, and establishing mechanisms for monitoring and enforcing compliance, including inspections and penalties for violators. The Forced Labour Regulation goal is to combat forced labor globally by leveraging the EU’s market power to encourage ethical labor practices.

A. Scope of application

This regulation will apply to all products entering into the EU market and all parties (economic operator, producer, supplier, importer, etc.) on the supply chain are concerned.

B. Controls and sanctions

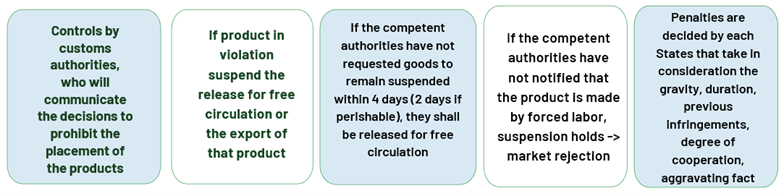

Compliance with the Forced Albor Regulations will be monitored by customs authorities and non-compliance will have the following consequences:

This new EU sustainability reporting landscape is part of a broader effort to promote sustainable development and address global environmental challenges, including in Asia. For several years, Asia has been undergoing significant developments: many nations have implemented their own environmental regulations, reflecting varying levels of commitment and approaches to sustainability.

But how is Asia EU-ESG ready and how will the EU regulations impact companies in China, Indonesia, India, Vietnam and India?

India

India, one of the world’s most dynamic emerging economies, is navigating with determination through the complex landscape of ESG. Endowed with remarkable cultural, social, and economic diversity, India faces unique challenges in sustainability and corporate governance. In this context, the adoption and implementation of ESG regulations play a crucial role in setting business conduct standards and promoting inclusive and sustainable economic growth.

Additionally, India is also responding to international developments, such as European ESG regulations, including the CBAM, which raises complex issues regarding the balance between business, environmental, and social imperatives. This interaction between national and international regulations provides insights into the challenges and opportunities India faces in its transition to a more sustainable and responsible economy.

ESG Regulatory Framework in India

In 2013, India became the first country to make corporate social responsibility (“CSR”) a legal requirement, mandating large companies to allocate a portion of their profits to it. Like many countries worldwide, India is thus firmly moving towards a future where sustainability and ESG play a central role in corporate governance.

1. Environment

The duty to protect the environment, both by the state and the individuals, is laid down by the Indian Constitution. India has a particularly rich legislative arsenal concerning environmental protection, with over 200 laws. As an illustration, this arsenal includes:

- The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974, aimed at ensuring the prevention and control of water pollution and maintaining or restoring water quality in the country;

- The Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981, concerning the prevention, control, and reduction of air pollution;

- The Environmental Protection Act, 1986 in India, a cornerstone of the country’s environmental protection and improvement, establishing environmental standards and regulatory mechanisms that significantly influence business practices and CSR responsibilities of companies.

- The National Green Tribunal Act, 2010, which created the National Green Tribunal tasked with efficiently and expeditiously adjudicating matters relating to environmental protection and forest conservation.

- Regulation related to hazardous waste management: many laws directly or indirectly address the issue of hazardous waste, such as the Factories Act, 1948, or the Public Liability Insurance Act, 1991.

These numerous laws, however, seem to have little effect on reducing the harmful effects of pollution and greenhouse gas emissions due to concern that a strict enforcement of laws on air and water pollution could disrupt of development projects that contribute to job creation and economic improvement.

2. Social

India is a party to many treaties, including the International Labour Organization (ILO) Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No.29) (since 1954), the Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105) (since 2000), and the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182) (since 2017). In accordance with international law it has criminalized most forms of modern slavery. Also, the Article 23 of the Indian Constitution prohibits forced labour and declares that the violation of this provision constitutes an offense punishable by law. Section 374 of the Indian Penal Code (which will be replaced by Article 146 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, a new penal code that will come into effect on July 1, 2024).

According to the Global Slavery Index[1], in 2021, 11 million people were still living in modern slavery in India, with a prevalence of eight per thousand inhabitants, placing India 6th out of 27 countries in Asia and the Pacific and 34th out of 160 countries worldwide (forced labor being the most common form of trafficking identified by the Indian government).

Although India displays a response rate (46%) higher than the regional average and has performed better than wealthier countries in the region, such as Japan and South Korea, in addressing the forced labor issue, the government still takes less than half the necessary measures to combat modern slavery.

3. Governance

The Companies Act, 2013 represents a major legislative milestone in India regarding CSR, defining the contours of corporate governance and CSR obligations.

Under Section 135 of the Companies Act, 2013, large companies are required to meet specific CSR obligations. This includes establishing a dedicated committee to oversee CSR initiatives, allocating annual funds representing at least 2% of the average net profit of the preceding three years to these activities, and publishing comprehensive annual reports on progress and fund allocation.

Compliance with government CSR guidelines is crucial, with companies closely following the prescriptions of the Companies Act, 2013. Any failure to meet these obligations can result in financial penalties and fines. Furthermore, the Companies Act, 2013 encourages companies to adopt a broader approach to CSR, beyond legal requirements, in favor of a corporate culture focused on sustainable development and overall societal well-being.

Ten years after the implementation of this obligation, the assessment is positive, although some call for better control systems and greater stakeholder involvement to ensure that CSR contributions are effectively utilized and reach intended recipients.

The rules of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”): SEBI, the Indian regulatory authority for financial markets, plays a central role in promoting transparency and corporate accountability in CSR. With its directives and guidelines, SEBI actively engages in enhancing the disclosure of CSR information by listed companies, thus providing investors with increased visibility into associated risks.

SEBI’s ESG information disclosure directive, also known as the “SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations” requires companies listed on Indian markets to disclose relevant information on ESG issues in their annual reports and other financial documents. This includes disclosure of company policies, practices, and performance regarding ESG, thus providing investors with increased visibility into related risks and opportunities.

Additionally, SEBI encourages the adoption of integrated reporting, which incorporates not only financial data but also information on ESG performance. This approach provides investors with a more comprehensive overview of the long-term value created by a company, taking into account its economic, environmental, social, and governance impacts.

The National Voluntary Guidelines on Social, Environmental, and Economic Responsibilities of Business (NVGs), published by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs in 2011, offer a valuable framework for companies wishing to integrate ESG principles into their business activities. Although these guidelines are not binding, they represent a crucial voluntary commitment to sustainable development and societal well-being.

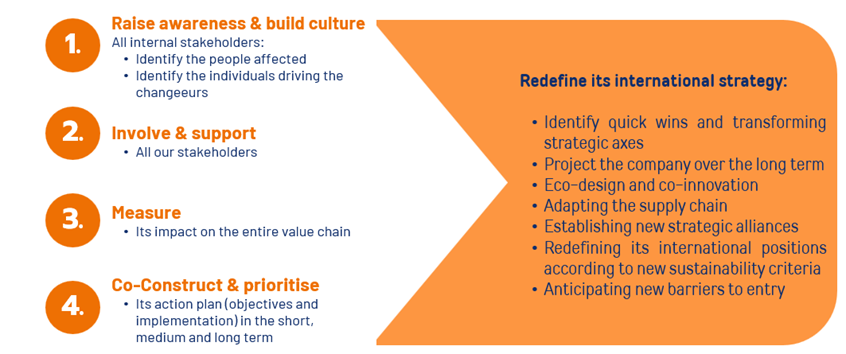

Impact of EU regulations on companies in Asia

The implementation of ESG principles and compliance with regulations can have a significant impact on companies operating in or trading with the EU. Companies must adapt to new standards and practices to maintain market access and competitiveness. This includes integrating sustainability goals into their operations, investing in cleaner technologies, and ensuring compliance with environmental and social regulations.

The CSRD will require subsidiaries of European companies or companies within the value chain of European partners to initiate data collection and sustainability report compilation to provide to their European partners or parent companies upon request.

Subsidiaries of European companies will benefit from available resources and a sustainability strategy that has been cascaded from the parent company whereas companies within the value chain of European businesses will need to carry out more preparatory work to meet requirements from their European partners to comply with the CSRD as they may lack guidance on European regulations. It is therefore paramount that companies educate themselves and seek guidance from their European partners to assess actions to be taken at their level to initiate data collection and sustainability report compilation.

Although the implementation of the CBAM by the EU directly impacts key industries, exporters must navigate the evolving scope of CBAM, which may expand to include indirect emissions and additional carbon-intensive sectors. To remain competitive in the EU and minimize the impact on production and export activities, exporters are urged to monitor CBAM progress closely, study reporting requirements for greenhouse gas emissions, assess financial implications, evaluate commercial opportunities for greener products, and implement decarbonization policies and greener production methods.

In addition to CBAM, exporters must comply with EU regulations on forced labor and deforestation to access the European market. The forced labor products ban requires rigorous due diligence to ensure no forced labor risks exist in the supply chain, including online sales. Similarly, exporters must provide evidence that their products have not contributed to deforestation or forest degradation. Exporters face the challenge of increased effort in tracking and tracing the origins of export goods, requiring training for all participants in the supply chain.

Companies that succeed in adapting to these changes can enhance their reputation and competitiveness in the global market. However, those that do not comply may face barriers to market entry and potential financial sanctions. The emphasis on sustainability and responsible business practices should drive innovation and create new opportunities for proactive companies facing environmental and social challenges.