Data protection and privacy frameworks are increasingly being developed globally. This is particularly the case in Asia: in the past two years, several key jurisdictions, including China, India, Indonesia and Vietnam have either introduced their jurisdiction’s first-ever comprehensive data protection laws or are updating and reforming their existing privacy laws. These regulations are very much influenced by, or borrow concepts from, the EU General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”) and set a high standard of compliance for organisations processing personal data.

Below is a snapshot of China, India, Indonesia, Singapore and Vietnam national approaches to privacy prepared by our Asia data privacy task force.

- Chine – Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL)

- Inde – Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA)

- Indonésie – Personal Data Protection Law (PDPL)

- Viêt Nam – Personal Data Protection (DPDP)

Our Asia data privacy task force. At DS Avocats, we have developed a strong expertise in data protection issues in Asia, enabling us to assist our clients in the development of their operations while taking into account their data compliance obligations. Our knowledge of the GDPR also allows us to bridge the needs of European based headquarters and the local subsidiary in China, India, Indonesia, Singapore and Vietnam.

The Personal Data Protection Act of Singapore 2012 (PDPA) came into effect on 2 July 2014 and provides a baseline standard of protection for personal data in Singapore. The PDPA’s main purpose is to protect privacy rights of individuals and regulate the collection and treatment of personal data by private organisations.

GDPR and PDPA:

While the GDPR is grounded in the philosophy of individual fundamental rights, particularly the right to privacy, and places a strong emphasis on data protection as a fundamental right of the individual positioning the safeguarding of privacy at the core of its concerns and recognizing the importance of preserving the confidentiality of personal data, the PDPA seeks a balance between data protection and facilitating business and acknowledges the significance of innovation and economic development while concurrently safeguarding privacy.

Both laws are comprehensive and provide a similar personal and extra-territorial scope. They both create a supervisory authority with wide-ranging investigation and corrective powers and the possibility to condemn actors to significant monetary fines in case of non-compliance. However, compliance with the PDPA does not necessarily mean the organisation is in compliance with the GDPR as there are differing requirements under the two regimes[1].

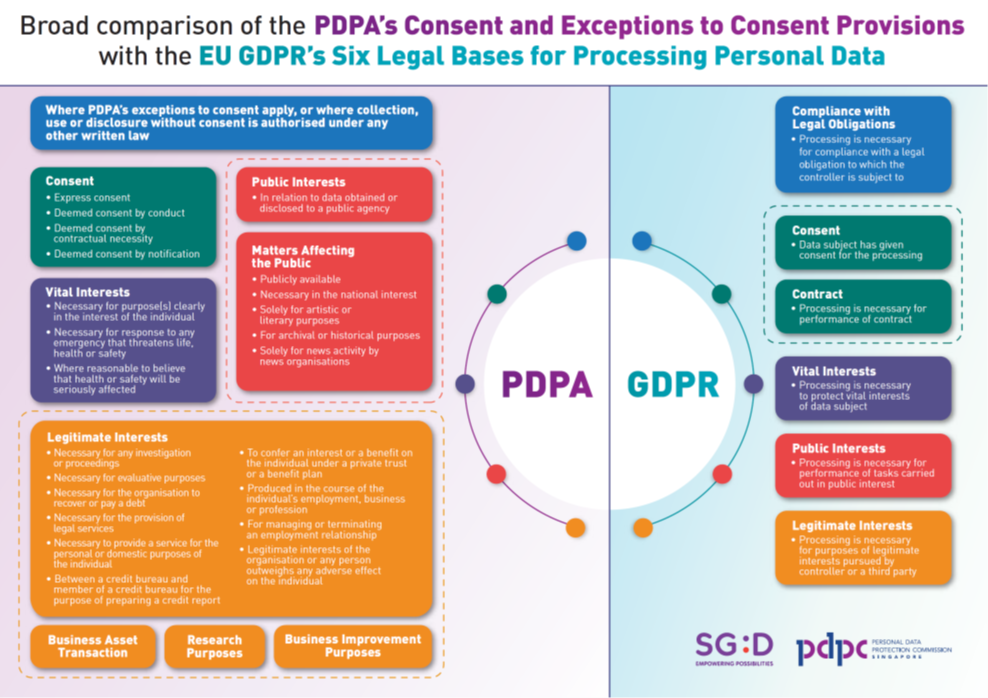

Below is an infographic developed by the Personal Data Protection Commission of Singapore (PDPC) illustrating the broad comparison between the PDPA’s exceptions to consent and the GDPR’s legal bases for processing of personal data.

[1] However, with the amendments introduced in the enhanced PDPA that came into effect on 1 February 2021, the exceptions to consent under the PDPA have been streamlined and categorised broadly in ways that are similar to the EU GDPR’s six legal bases for processing of personal data.

Other differences are:

- While the PDPA excludes public agencies and organisations acting on behalf of it, the GPDR applies to both private and public bodies.

- The PDPA grants a narrower protection to individual compared to the GDPR.

- While the GDPR applies to all businesses that process personal data of EU data subjects, regardless of where they are located, the PDPA applies to any organisation, excluding public agency, that process personal data in Singapore.

- Although both legislations grant people the right to be informed of the conditions under which their data is collected and used, the right to object to the collection of their data, the right to access data that has been collected and to modify it, the RGPD goes further by notably allowing people to obtain the deletion of their personal data that has been collected. The PDPA for its part remains silent on this point. Thus, companies that have collected data are not required to delete the data collected if requested to do so.

Présentation du PDPA

| Legislation | Personal Data Protection Act 2012 (No.26 of 2012) (“PDPA”) Specific guidelines for certain sectors: telecommunications/real estate agencies/ educations / healthcare / social services / transport services / management corporation / Specific regulations for certain sectors: banking/ healthcare / life insurance |

| Regulator | Personal Data Protection Commission (PDPC) |

| Scope | Applies to all organisations (including any individual, company, association or body of persons, corporate or unincorporated, whether or not formed or recognized under the laws of Singapore) that carries out activities involving personal data in Singapore, unless they fall within the category of organisations expressly excluded from the application of the PDPA: • Individuals acting in a personal or domestic capacity; • Employees acting in the course of his or her employment with an organisation; • Public agencies; and • Organisations in the course of acting on behalf of a public agency in relation to the collection, use or disclosure of personal data. |

| Definition of personal data | “personal data” means data, whether true or not, about an individual who can be identified — (a) from that data; or (b) from that data and other information to which the organisation has or is likely to have access;” PDPA does not define special categories of data PDPC have considered in several decisions the concept of more sensitive data, including: medical data, financial data, bankruptcy status, drug problems and infidelity |

| Obligations under the PDPA | Personal data protection principles: • The consent obligations (sections 13 to 17) • The purpose limitation obligation (section 18) • The notification obligations (section 20) • The Access and Correction Obligations (sections 21, 22 and 22A • The Accuracy Obligation (section 23) • The Protection Obligation (section 24) • The Retention Limitation Obligation (section 25) • The Transfer Limitation Obligation (section 26) • The Data Breach Notification Obligation (sections 26A to 26E) • The Accountability Obligation (sections 11 and 12) |

| Parties involved | Data controller: the PDPA does not use the term ‘data controller’. Instead, it uses the more general term ‘organisation’ to refer to the entities that are required to comply with the obligations prescribed under the PDPA. The term ‘organisation’ broadly covers natural persons, corporate bodies (such as companies) and unincorporated bodies of persons (such as associations), regardless of whether they are formed or recognised under the law of Singapore, or are resident or have an office or place of business in Singapore Data processor: the term ‘data processor’ is not used in the PDPA, but an equivalent term ‘data intermediary’ is used. A ‘data intermediary’ is defined as an organisation which processes personal data on behalf of another organisation but does not include an employee of that other organisation. For more information on the obligations of data intermediaries, see also section on personal scope above |

| Rights of data subjects | Provide individuals access to and correct errors to their personal data |

| Security | Security arrangements reasonable and appropriate in the circumstances to protect personal data and prevent unauthorised access, collection, use, disclosure, copying, modification, disposal or similar risk |

| Requirement for consent | Consent obligation (sections 13 to 17): organisations are required to obtain individuals’ consent to collect, use, or disclose their personal data unless such collection, use, or disclosure is required or authorised under the PDPA or any other written law Consent is not required for the collection, use, and disclosure of personal data where the specific exceptions in the First Schedule and the Second Schedule to the PDPA apply, for example where the collection, use, or disclosure of personal data about an individual is: • Necessary for any purpose which is clearly in the interests of the individual, and (i) consent for the collection, use, or disclosure cannot be obtained in a timely way; or (ii) the individual would not reasonably be expected to withhold consent • Publicly available • In the national interest • In the legitimate interests of the organisation or another person, and the legitimate interests of the organisation or other person outweigh any adverse effect on the individual An organisation is further required to state the purposes for which it is collecting, using, or disclosing the data under the Notification Obligation Individuals can be deemed to have given consent when they voluntarily provide their personal data for a purpose, and it is reasonable that they would voluntarily provide such data. The PDPA provides for three different forms of deemed consent: • Deemed consent by conduct • Deemed consent by contractual necessity • Deemed consent by notification. Consent should be written or in electronic form Consent can be withdrawn at any time by an individual upon reasonable notice to the organisation |

| Impact assessment on data processing | Cross-border transfer of data and impact on assessment of overseas transfer Organisation may transfer data if: • They comply with the PDPA while the transferred data remains in their possession; • The recipient is bound by legally enforceable obligations to provide protection comparable to that under the PDPA |

| Breach notification | PDPC’s Guide to Managing Breaches 2.0 Organisations are advised to notify the PDPC and/or affected individuals of data breaches that is of a significant scale or is more likely to result in significant harm or impact to the individuals to whom the information relates |

| Sanctions | Fines not exceeding S$1,000,000 or 10% of the annual turnover if it exceeds S$10,000,000 |